Fuller v. Bemis and the Failed Prehistory of Choreographic Copyright

In the 1890s, famed dancer Loïe Fuller had her first major success with the “Serpentine Dance,” a variation of the popular “skirt dances” of the day. But should she keep it for herself? When others started dancing an imitation of her choreography she would try, and in the process give chreographic copyright a false start a half century before it would succeed.

The case of Fuller v. Bemis is fairly well-known to historians of copyright and dance, and there’s already been an excellent post about it on IPKat. Anthea Kraut has also written both an article and a book that focuses, in full or part, on this case. In that case the Fuller sued dancer Minnie Renwood Bemis for copying her “Serpentine Dance” in 1892. However, the Southern District of New York dismissed her claim and found any copyright in the dance invalid.

“A stage dance illustrating the poetry of motion by a series of graceful movements, combined with an attractive arrangement of drapery, lights and shadows, but telling no story, portraying no character and depicting no emotion, is not a ‘dramatic composition’ within the meaning of the Copyright Act.”

Fuller v. Bemis, 50 F. 926, 929 (C.C.S.D.N.Y. 1892)

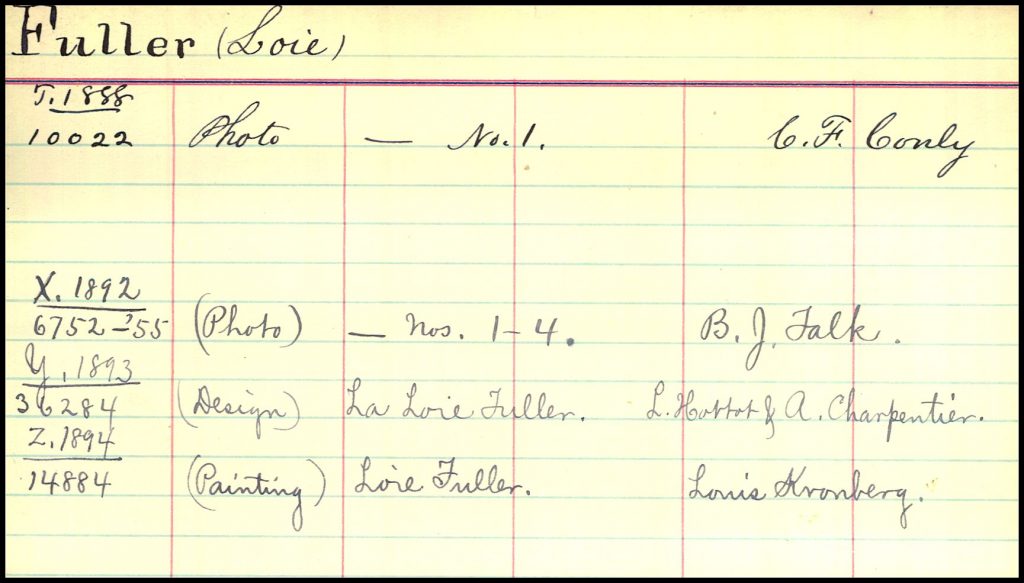

However, had Fuller received a registration? No registration is indicated in the Virtual Card Catalog.

Fuller is now seen as a pioneer in modern dance, and as mentioned above her lawsuit has been studied by historians of dance, and is part of the excellent bibliography on copyright and choreography by Julie Van Camp from 1994. However, the lawsuit is also interesting from a copyright history perspective, since Fuller was attempting suit based on a rejected claim for registration, and is possibly the first such lawsuit.

Fuller clearly understood the legal complexities of her suit, and hired the experienced copyright firm of Lewinson and Falk to handle the case. Benno Lewinson was a recognized authority on copyright law, having litigated cases including Press Publishing Co. v. Falk. Anthea Kraut and the National Archives both provided parts of the case file, which I’ve posted here, which tells a fuller story of the case.

At the time, the law (section 86, 1870 copyright act) covered a wide but discrete array of types of works – namely book, map, chart, dramatic or musical composition, engraving, cut, print, or photograph or negative thereof, or a painting, drawing, chromo, statue, statuary, and models or designs intended to be perfected as works of the fine arts. However, that same law (section 101, 1870 copyright act) only provided for statutory performance rights for dramatic compositions. That changed in 1897 with the addition of music, and prior to this performance rights were available at common law for unpublished musical compositions. I’m not sure if unpublished choreography would have had performance (or any) rights at common law at the time, although it would have been an interesting argument. However, it was not an argument Fuller had available, as she had already chosen to publish her Serpentine Dance. Or at least, she chose to publish it for purposes of copyright – it isn’t clear if it was widely distributed. No copies appear in Worldcat, for instance, and the copy included with the case file doesn’t indicate distribution or even give a price. Arguing the case at common law would have been a fascinating alternate history, but once she and her attorney chose to attempt to register the copyright, that option was foreclosed.

We don’t have a copy of Librarian of Congress Ainsworth R. Spofford’s response to Fuller’s attorneys, but Bemis’s attorney’s contacted Spofford, and his response was unequivocal.

Gentlemen,

In reply to yours of 26th – the entry of Copyright on “a Serpentine Dance,” by Marie L. Fuller, was not made – for the reason that it does not come within the designation of any of the articles which are lawful subjects of copyright.

The two copies purporting to be this “Dramatic Composition” are nothing but written directions for dances, tableux, poses, etc, without a word of dialogue or literary composition of any kind.

As this matter cannot be viewed as a “dramatic composition” in any sense, the claim to record copyright thereon was disallowed, and therefore returned to Messrs. Lewinson & Falk, attorneys.

Very respectfully, AR Spofford, Librarian of Congress

Letter from Ainsworth R. Spofford, Librarian of Congress, to Messrs. Brittan & Gray, May 27, 1892.

As I explore in my piece Examining Copyright, forthcoming in the Journal of the Copyright Society of the USA, applications for copyright registration had been denied before, although documentation is sparse. However, the actual statute does not seem to contemplate a registration being denied, and as such it does not indicate that a suit may be brought after registration is denied. Perhaps because of this difficulty, the opinion does not focus on it, and acts as if formalities of copyright had been validly perfected.

Instead, the short opinion (most of the printed opinion is a reprint of the work and arguments of counsel) is focused on distinguishing Daly v. Palmer. In that case from 1868, which Bruce Boyden has written about, the court had found the “Railroad Scene” pantomime of a person tied to railroad tracks in peril and being rescued was copyrightable. The Court held that “[i]t is essential to [a dramatic] composition that it should tell some story,” and while the Railroad Scene did tell a story, the abstract dance of Loïe Fuller did not.

The first registration of choreography for copyright would not be until 1952, when Hanya Holm received one for her choreography for Kiss me Kate. In a study a few years later on copyright in choreography, prepared as part of the Office’s Revision Studies project, the Copyright Office explained that only dramatic choreography was eligible for copyright as choreography could only be registered as a dramatic work, pursuant to Fuller v. Bemis. Nondramatic choreography would only be registrable for copyright when the 1976 Copyright Act became effective on January 1, 1978.