The Map, the Man, and the Lawsuits: How a Divorce Case Helped Make Copyright Law

Ownership of a physical object does not include the copyright for the work embodied in that object – be it a master tape, film negative, or a copperplate intaglio of a map. The root of this doctrine is a series of cases before the Supreme Court, where the Court held that the copyright “is wholly independent of, and disconnected from,” the physical object it is embodied in. Stephens v. Cady, 55 U.S. (14 How.) 528, 532 (1853). Two years later the Supreme Court again weighed in, holding that copyrights (and patents) were not subject to seizure by state officials. Stevens v. Gladding, 58 U.S. (17 How.) 447 (1855) (same party, Stephens was a misspelling). These cases are well-known – they’re the first cases involving copyright in maps before the US Supreme Court, and they remain important precedents. But the story behind them is obscure – even the transcripts of record filed with the Supreme Court only hint at the details of this case. So, naturally, I started digging – and what I found is a story of infidelity, divorce, alimony, and maps.

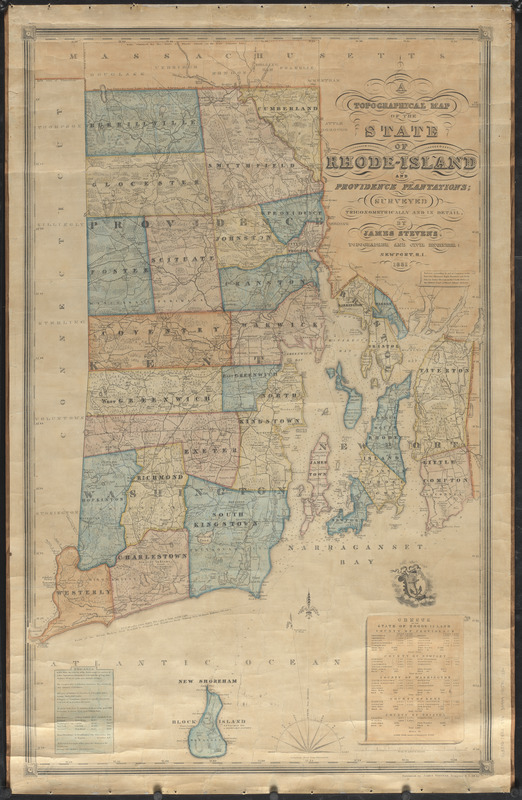

The Map

In the early 1820s James Stevens was a civil engineer and “topographer” living and working in the city of his birth – Newport, Rhode Island. Following a series of events, James took on the project of making the first ever map of Rhode Island, something urgently needed, and already completed for other states decades earlier. In 1829 James finally won state funding through a lottery, and on January 22, 1830 he registered the copyright for his map and also a book which does not seem to have been finished or published, entitled “Geography of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations containing separate Maps of each of the towns in the State of Rhode Island in which maps are given the Indian names of places and other historical facts.” Included in the registration is the opening of Lay of the Last Minstrel, Canto VI, by Sir Walter Scott, although it is unclear if if it is part of the title, of the title page, or just an embellishment.

Breathes there the man, with soul so dead,

Who never to himself hath said,

This is my own, my native land!

Although he presumably meant to publish the two works shortly after the registration, that was not meant to be, especially after his materials were stolen from his carriage the following year, with the papers burnt and instruments and sold for scrap metal. Although the map is generally dated to 1832, James stated in a later court filing that he had deposited his map with the clerk on April 23, 1831 – perhaps it was an incomplete version. In litigation over a decade later, Sarah Sherman (not his wife, much more on this later) stated that James’s son had delivered two copies to her, and she delivered them to the clerk of the court on February 14, 1833. The clerk apparently indicated that he had already received one, but with this deposit two copies were properly deposited, although they may have been late.

The map was a success, and served its purpose well as a complete map of Rhode Island. James Stevens would never again work on another project of historical significance, and instead settled into what seems to be a quiet professional life as a civil engineer – newspapers report on him doing things like studying an area for a railroad bridge, and donating a model yardstick, and writing a letter to the editor about an old book he owned. However, his personal life would be much more eventful, and the consequences of his actions would lead him multiple times to the United States Supreme Court.

The Man

James Stevens was born around 1789 in Newport, RI, a city of under 8,000 people in these times, to John and Mary Stevens. On July 25, 1812, James married Sarah Sherman, daughter of Preserved and Eunice Sherman of Portsmouth, RI. They chose names from ancient mythology for his children, for instance naming a son Appollo (how it is spelled in the records). However, many of the children died before reaching adulthood – we have a record of their only daughter Minerva dying at the age of 15 in 1836, but the divorce record states that she was not the only child they lost young.

By 1835, James was in a adulterous relationship with another woman, also improbably named Sarah Sherman, and had a two children with her by that year, named Juno and Achilles Stevens . This second Sarah Sherman was 23 or so years his junior (so almost exactly half his age in 1835). He had known her for longer – in early 1833, as mentioned above, she had deposited copies of the map with the clerk of the US District Court, and one questions why James had a 20-year old doing that unless he already knew her fairly well. One suspects she may have been a relative of his first wife, but I can’t confirm it.

The Supreme Court transcript of record does not give much detail on what happened next, but Christopher J. Carter at the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court’s Judicial Archives branch was good enough to supply the case papers, and I’ve shared them here (you can also see the divorce judgment on FamilySearch). James and his first wife attempted to reconcile it seems, but by 1843 his first wife moved to Fall River, MA, and filed for divorce, on the basis of infidelity with the second Sarah Sherman, and unknown “divers other persons.”

There doesn’t seem to have been much doubt as to the facts of the situation, but the damning testimony of Joseph Read of Fall River could not have helped – he testified in response to an interrogatory that he had been riding in a carriage with James Stevens and they came upon a child upon which James explained “this is one of my second crop.” Joseph Read further testified that James was already cohabiting with the younger Sarah Sherman. James asserted in response that he was living with his first wife as late as 1842, which seems a rather weak response. The Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts sitting in Taunton ordered the marriage dissolved, gave (the first) Sarah custody of their younger son Euclid, and ordered alimony of $3 weekly, paid quarterly.

The Lawsuits

Following the divorce, James did not make the required alimony payments. Sarah brought a suit to enforce the debt, and in March of 1846 was awarded $194.23 in damages and costs. The Supreme Court transcript of record states what happened next, from the answer filed in federal court.

Sarah Stevens, of Fall river, in Massachusetts, on the 1st day of April, A. D. 1846, having recovered a judgment against said James Stevens for one hundred and seventy-six dollars damages, and eighteen dollars and twenty-three cents, costs of suit, before the court of common pleas, held at Taunton, in and for Bristol county, in said State of Massachusetts, on the second Monday of March, 1846, which court had jurisdiction of said cause, took out from said -court an execution duly issued by said court under the seal thereof and signed by the clerk thereof, and dated the 11th day of April, 1846, all in due form of law, ready to be produced and shown as this honorable court may direct, commanding the sheriff of said county of Bristol, that of the goods, chattels, or land of the said James Stevens, within said county, he should cause to be paid and satisfied unto said Sarah Stevens, or the value thereof in money, the said sum of one hundred and ninety-four dollars and twenty-three cents in the whole, and twenty five cents for said writ of execution, and thereof also to satisfy himself for his lawful fees in the premises, and for want of such goods, chattels, or lands of the said James Stevens, by him shown or found within his precincts to the acceptance of the said Sarah, the said sheriff was commanded in and by said writ to take the body of said James Stevens, and him commit to the county jail at Taunton or New Bedford, in said county of Bristol, and him detain in custody within said jail until he should pay the sum above mentioned with the fees thereon, or be lawfully discharged by said Sarah or by order of law, and that said sheriff should make due return of said writ, with his doings thereon; all which will more fully appear by the records and files of said court of common pleas, for said Bristol county, copies of which are ready to be shown and produced as this honorable court may direct.

And this deponent further answering saith, that said James Stevens neglected to pay said debt and satisfy said execution, and left or turned out at Fall River aforesaid, within the precincts of the sheriff to whom said execution was delivered to be collected, and then and thereby turned out to said sheriff said copperplate on which said map was engraved, by leaving or placing the same where said sheriff might levy on the same in default of payment of said execution; and because said James Stevens neglected to pay and satisfy said execution, and left said property to satisfy the same, said sheriff, at Fall River aforesaid, on or about the 25th day of April, 1846, levied said execution upon said copperplate, so as aforesaid engraved for printing said maps, and duly posted and advertised the same for sale to satisfy said execution, and, after the expiration of more than four days after said levy, and, after giving said James Stevens full opportunity to pay said execution, and save said property from being sold if he had chosen so to do, said sheriff, on or about the 6th of May, 1846, at Fall river aforesaid, sold at public auction said copperplate so as aforesaid engraved with said engraving thereon, to this defendant, Isaac H. Cady, for the sum of two hundred and forty-five dollars, he being the highest bidder for the same; and on the 9th day of May, 1846, this defendant paid said sheriff said sum of two hundred and forty-five dollars for said plate, and received the same from said sheriff’s his own property,

Supreme Court Transcript of Record, Stevens v. Cady

In other words, James failed to pay and the copperplate was seized and sold to Isaac H. Cady to pay James’s debts to his former wife (some other goods including a printing press were also seized). James was also arrested but absconded back to Rhode Island, beyond the reach of the Massachusetts court (in a pleading from 1848 he was living in Stonington, CT, perhaps to avoid enforcement of the judgment in Rhode Island). Following the sale of the copperplate, Isaac Cady commissioned a revised second edition of the map, and James Stevens sued Cady, and separately and the booksellers Royal Gladding and Isaac Proud of Providence, RI, for copyright infringement, in equity, requesting an injunction and accounting for profits. James also sued Gladding & Proud for $4,000 in a qui tam proceeding (suing on behalf of the US Government, now mostly seen in whistleblower/false claims suits).[1] Everyone agreed James had filed the copyright registration for the map and it was still within its 28 year initial copyright term, but the copperplate had been seized by the sheriff for nonpayment of his debts. Had the copyright also been seized?

In 1849 the Cady case was argued in the US Circuit Court for the District of Rhode Island (then a trial court).[2] James Stevens represented himself pro se, and in 1850 Justice Levi Woodbury, riding circuit, ruled against James, holding that the sheriff’s seizure and sale included at least a license to print from the copperplate. Justice Woodbury noted that the scrap value of the copperplate was $10, suggesting that the remaining $240 of the amount paid was for the ability to use it for making prints. However, Judge Pitman from the District Court, sitting with him, disagreed, and the division of opinion entitled James to take the case to the U.S. Supreme Court. A year later Justice Woodbury died, meaning James would not have the Justice who ruled against him deciding the case.

In 1852 the Cady case reached the U.S. Supreme Court (it isn’t clear why the name is spelled Stephens here, but that seems clearly incorrect, and is probably a printer’s error). James again made his own argument, this time in print, while no appearance was made for Cady et al. With no opposition made, the Supreme Court ruled for James, holding that “the property acquired by the sale in the engraved plate, and the copy-right of the map secured to the author under the act of Congress, are altogether different and independent of each other, and have no necessary connection.” In other words, the copperplate was no more than scrap metal to Cady, because they had no ability to use it to make copies. In retrospect they doubtless should have appeared before the Supreme Court, and their woes in litigation were only beginning.

Following the win before the Supreme Court, James, this time represented by counsel, continued the fight against Gladding and Proud, arguing that he was entitled to remedies including an accounting of profits from Gladding as well as an injunction. The Circuit Court, this time with Justice Benjamin Robbins Curtis riding circuit (one of the leading early IP experts and brother of the author of the first American copyright treatise), ruled that James was entitled to injunction but not the accounting. And back to the Supreme Court James went, once again successfully, winning an injunction, accounting for profits, and costs of $71.15. (The transcript of record for this case was not on Gale’s database of Supreme Court Records and Briefs, so I scanned it myself from the microfilm – thanks to Alicia Jones at the SIU Law Library for assistance)

Somewhat surprisingly, Justice Curtis then wrote the opinion reversing his own prior ruling, and finding that an accounting was in fact due to James. The case then back to the federal Circuit Court in Rhode Island again. This time, slightly over a decade after the sheriff’s sale of the plate in 1846, James won the right to both his injunction and an accounting for profits, to be determined by a special master.

In 1848 the qui tam suit had fizzled out, when a jury had found Gladding and Proud not guilty of copyright infringement. However, with the win before the Supreme Court in the action at equity, James sought to revive it – one suspects that his actual monetary result from the accounting was fairly minimal, and he wanted the much greater recovery of $4,000 from the qui tam suit. The Supreme Court ordered the record be transmitted on writ of error from Rhode Island, and reviewed this case to determine if the jury’s verdict should be revisited. James for his part filed a short document indicating that the Court’s decision in the Cady case was “decisive” in the qui tam action as well. However, in 1857 the US Supreme Court upheld the jury verdict, noting that “[i]t is to be regretted that [James], in undertaking to manage his own case, has omitted to take the necessary steps to protect his interest.” In other words, James had been representing himself, and his own procedural mistakes had cost him the case – in this case there were depositions of Archibald Dick and Henry Wilson, “engravers and copper plate printers,” testifying that between 1,300 and 1,400 of the revised maps were made. Since qui tam damages were per copy and exact number was vital, but James had failed to include these depositions with the certified record, and thus the Supreme Court had no basis for granting the writ of error. Gladding and Proud were also granted costs of $58.39.

In 1859, James was once again suing Gladding & Proud, but this suit was interrupted by his death at the age of 73, on May 3, 1860. With their children nearing adulthood, James had married the second Sarah Sherman in 1852, and she survived him along with their children James’s first wife also survived him, but not for long, as she died only a year later – after the divorce she’d been working as a housekeeper in Fall River, MA, and had lost her son Appollo in 1859. The second Sarah Sherman lived with her daughter Juno and her husband George as of the 1860 census following her husband’s death, but she spent her last years in the Newport State Insane Asylum, where she died in 1888.

What Does It All Mean?

Understanding this background, the Stevens copyright cases look sharply different than they did before…a prominent if eccentric man left his wife for a younger woman, refused to pay alimony in an era where employment options for women were limited, and then spent the last 14 years of his life fighting those who had paid his wife for his debt. But it raises a deeper question as well – does the disaggregation of intellectual property from the material object it is embedded in further work to disadvantage those who with less power in the negotiating dynamic? There is currently a class action pending in New York federal court about whether recording artists have the power to terminate the transfer of their rights in their sound recordings made 35 years earlier and recover those rights for themselves. However, even if successful, they will not gain the ownership of the master tapes themselves, which will remain property of the record company. If they wish to do a remastering and re-release of their music, they will still need to make a deal with the (usually) big record company that owns those tapes. The object is only worthwhile to someone who has the rights, and the rights are of minimal value without the object, and the disaggregation of rights will benefit players with more power.

Further, this all remains good law. Stephens v. Cady and (the first) Stevens v. Gladding are still frequently cited for this very proposition, without knowledge of their context. It remains unclear if a copyright can be split as part of a divorce – many state courts (including California) have tacitly or explicitly done so, but the 5th Circuit has held that while the royalty stream from a copyright can be divided in a divorce proceeding, the exclusive rights enumerated at 17 USC 106 (reproduction, distribution, derivative works, public display/performance, digital phonorecord) cannot. A note on the subject has observed the split between family law scholars and copyright scholars on the issue. My colleague Angela Upchurch has also written on the closely related issue of patents and marital property, exploring the conflicts between federal law and state law on the subject.

In a way, James’s first wife got a lucky break – Isaac Cady didn’t know he was buying a piece of metal encumbered by an adverse copyright. I haven’t found anything about Isaac Cady trying to get his money back, and indeed he may have quietly relied on Sarah Stevens to be a friendly witness. However, any subsequent woman in her condition would not as as lucky, and elements of this have survived to this day.

[1] Qui tam remedies were part of the Statute of Anne in 1710 in England, where a party could receive damages of 1 cent per copy, split equally between the crown and the plaintiff. Section 3 of the 1802 Copyright Act added them to American copyright law for prints from engravings and similar works, with damages of $1 per copy, split between the United States and the plaintiff. Section 7 of the 1831 Act retained this provision, as did section 100 of the 1870 omnibus IP act. In place of the qui tam provisions the 1909 Copyright Act established what we now call statutory damages.

[2] This is reported as Stevens v. Gladding – the reported case indicates that the court had earlier decided the issue in the equity case against Cady, and the qui tam action against Gladding gave them Justice Woodbury the opportunity to read his opinion to the jury, which was then reported.