Counting Copyright Registrations Before 1870

This past spring/summer, my article (coauthored with Richard Schwinn, Ph.D) entitled “An Empirical Study of 225 Years of Copyright Registrations.” This post is part of a series studying particular parts of my paper, and sharing in greater detail than I could there some insights.

When I first joined the Copyright Office as the Abraham L. Kaminstein Scholar in Residence, I had figured I’d focus on the era of the copyright card catalog, which is 1870-1978 (really 1898-1978). And I did spend quite a while on that period, which I’ll go into in a subsequent post. However, I also found myself diving deeper into the pre-1870 copyright registrations, where registration was accomplished by deposit of a title page and filling out a prescribed form of registration with the clerk of the local United States District Court. Little is known about these registrations, and I set out to try to learn more about them and make them available. Many have heard that the project to scan these records, (mostly) held by the Rare Book Room of the Library of Congress is currently underway. In fact, the first part of this project – the roughly 50,000 title pages from this period – has recently been made publicly available.

In this post I intend to:

- Give the history of the pre-1870 copyright records themselves;

- Describe how Dr. Schwinn and I estimated statistics of these records;

- Provide information and analysis about these statistics; and

- Shine light on what was being registered for copyright before 1870.

Until 1870, the clerks of the individual US District Courts were required to maintain their copyright records. In 1870, Congress passed an omnibus revision of the IP laws. Copyright was transferred to the Library of Congress by §85 of that law, while §110 provided:

That the clerk of each of the district courts of the United States shall transmit forthwith to the librarian of Congress all books, maps, prints, photograp[h]s, music, and other publications of every nature whatever, deposited in the said clerk’s office, and not heretofore sent to the Department of the Interior, at Washington, together with all records of copyright in his possession, including the titles so recorded, and the dates of record.

Most of these records made it to the Library of Congress, but a few thousand did not. Those records which made it were held by the Library’s Copyright Department, which became the Copyright Office in 1897. In 1934, Ruth Shaw Leonard recounts being shown “a disordered array of dusty volumes and boxes” comprising “the copyright records from the various United States District Courts from 1790 to 1870.” According to Ms. Leonard these records were transferred to the Rare Book section of the Library of Congress in 1939. That year Martin A. Roberts, the Chief Assistant Librarian, published Records in the Copyright office deposited by the United States district courts covering the period, 1790-1870, which has remained the main descriptive work about the pre-1870 records. In this work Roberts estimated that there were a total of 150,000 registrations in the District Court from 1790 to 1870, and this has remained the only real estimate available of pre-1870 copyright registrations. Indeed, to this date the annual report of the US Copyright Office provides this number, and provides yearly numbers for 1870 forwards.1 In 1969 G. Thomas Tanselle published Copyright Records and the Bibliographer, which includes a substantial section describing the pre-1870 records.

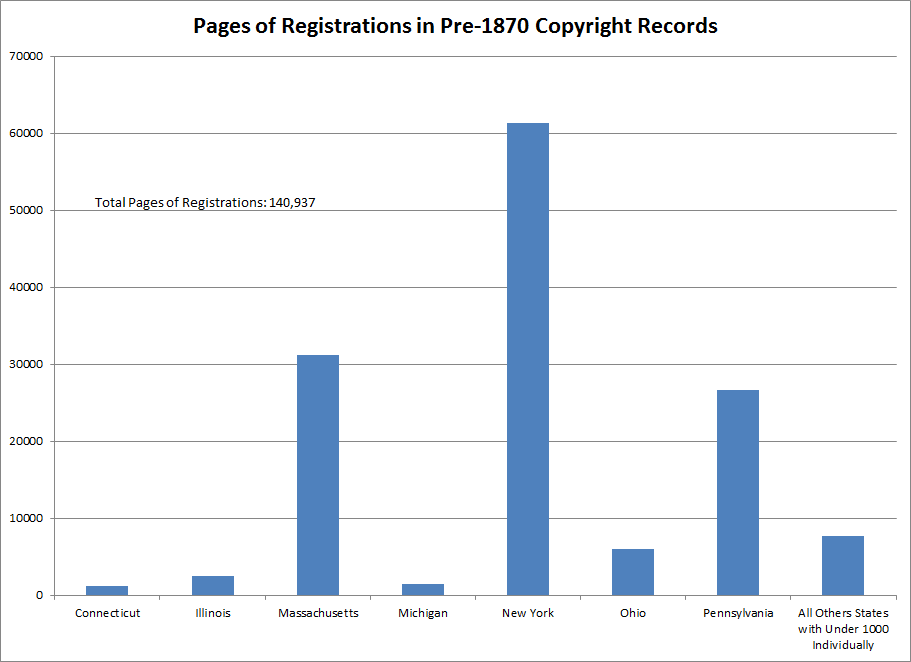

In the late 1970s a microfilm was made of the ledger books containing the original registrations, and a finding aid was prepared for the microfilm. Helpfully, the finding aid says exactly how many pages there are in each volume, and what dates the volume covers. Upon finding this document, I realized that I could get a reasonably good approximation of the total numbers of registrations, both by state/jurisdiction and nationally. Accordingly, I converted the finding aid into a csv file for purposes of analysis. This showed a total of 140,088 pages of copyright registrations, distributed mostly in just a few states. I then added the additional 849 pages I found in other repositories.

Accordingly, it looks like the estimate Martin Roberts gave of 150,000 registrations is pretty accurate. In states with high volumes it was typically one registration on a pre-printed sheet on each page, whereas states with a lower volume of copyright registrations often wrote them out by hand, typically 1-2 per page. In addition, we know hundreds (if not a few thousand) registrations are still missing from places including Maryland (until 1831), Louisiana (until 1851), the District of Columbia (until 1845), Virginia (until 1863, with caveats), and Connecticut (until 1804).

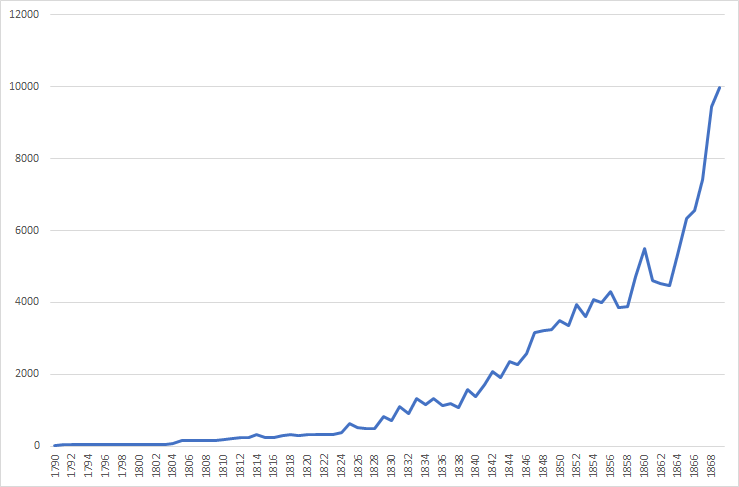

However, I wanted to do more, and I had an inkling that I could connect this data to the Library of Congress/Copyright Office Data for 1870-1977 that I’d also been compiling. My coauthor on the paper, Richard Schwinn, used his skills in statistics and R to turn that finding aid into estimated totals per year, which shows us the rise in copyright registrations in America from 1790 to 1870. His processed version of the data is this csv file.

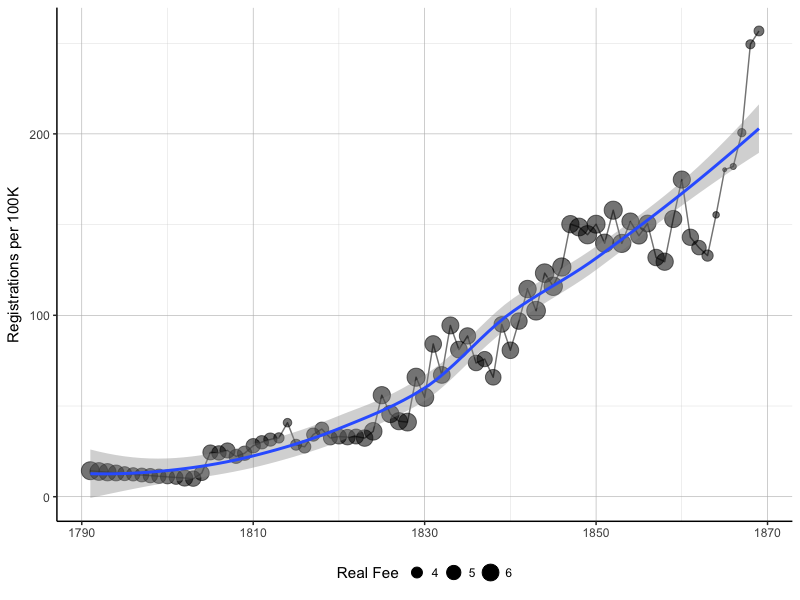

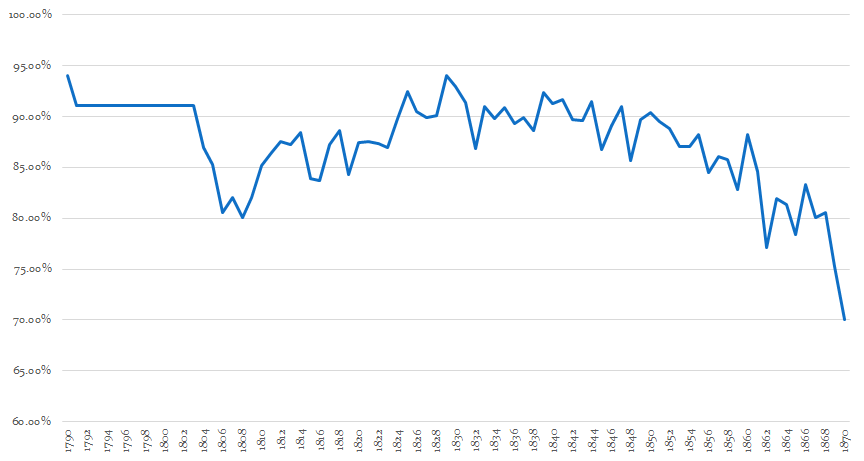

However, that isn’t necessarily helpful, because it ignores (a) the changing population of America and (b) the impact of inflation on the registration fee. To this end, Dr. Schwinn put together a single chart that shows all of this in graph (this one is in our paper).

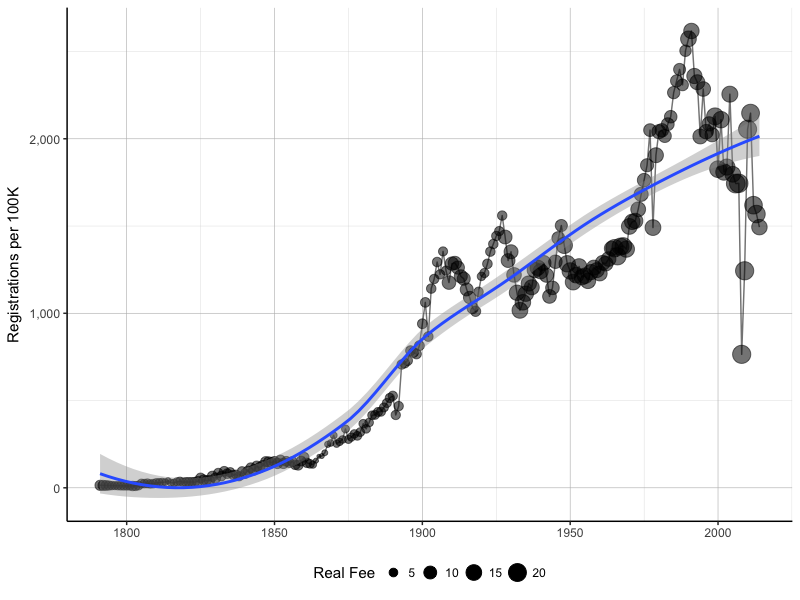

You might be wondering how this fits into copyright registration in American history more generally, and accordingly here’s the 1790-2015 chart from our paper. You can see that even adjusting for population copyright registration wasn’t that common before 1870. It’s important to note the different scale of the two graphs – the 1790-2015 graph is about 10x the magnitude of the 1790-1870 graph.

We’re really proud of this data and our findings – until now no-one has had yearly data on copyright from this period, and this this isn’t just of antiquarian interest. By having data on yearly registrations for 1790-2015, we were able to assess whether the 1831 Copyright Act (which extended the copyright term, reduced formalities, and expanded the subject matter of copyright) led to more copyright registrations. We found that it did, but once you account for the effect we found associated with copyright term, the 1831 Act was no longer a significant impact on copyright registrations. In other words, the 1831 Act led to more registrations because of longer term, not because of reduced formalities, which was not what we expected. We had expected that the removal of several very annoying features of the 1790 Act like the requirement of publishing notice of copyright in a newspaper would have an independent impact on copyright registrations.

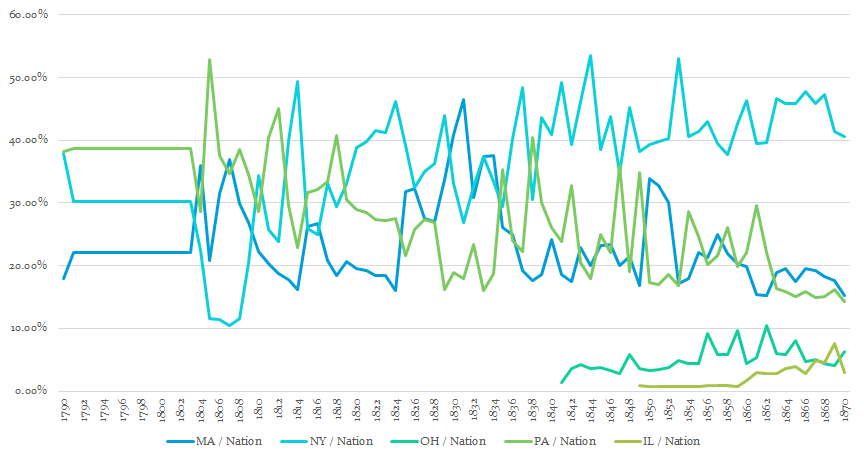

We don’t go into this in our paper, but we also have data on individual states until 1870, which is itself somewhat interesting. This is particularly so for states which had a substantial volume of copyrights – so a small cluster of registrations likely isn’t skewing the data.

As mentioned, New York, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts were an overwhelming percentage of registrations for this entire period. The dip from over 90% in 1850 to under 80% during the Civil War largely reflects the increasing importance of urbanized centers in Ohio and Illinois. This is shown when you break this out into individual states and include those.

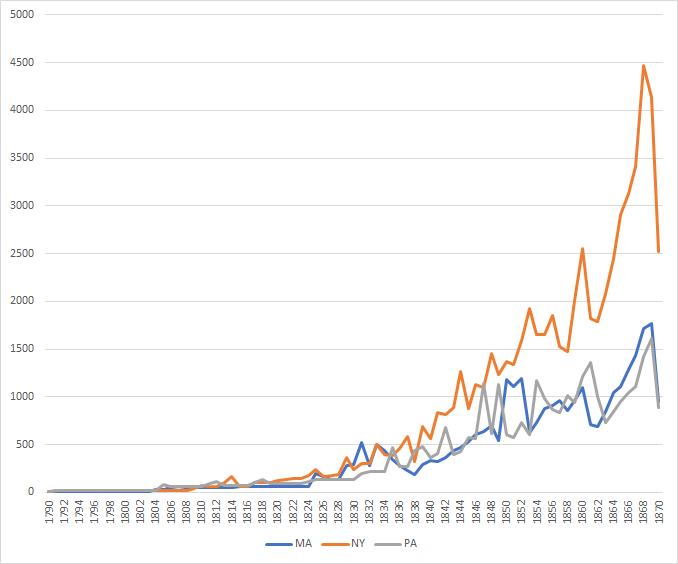

This in turn hints at the increasing importance of New York in particular as a publishing center, as both Massachusetts and Pennsylvania decreased from their peak substantially. This is a bit less apparent looking at the raw registration numbers per state, which nonetheless give a good sense of the scale of publishing in these states (note that 1870 is a stub year so the decline isn’t meaningful).

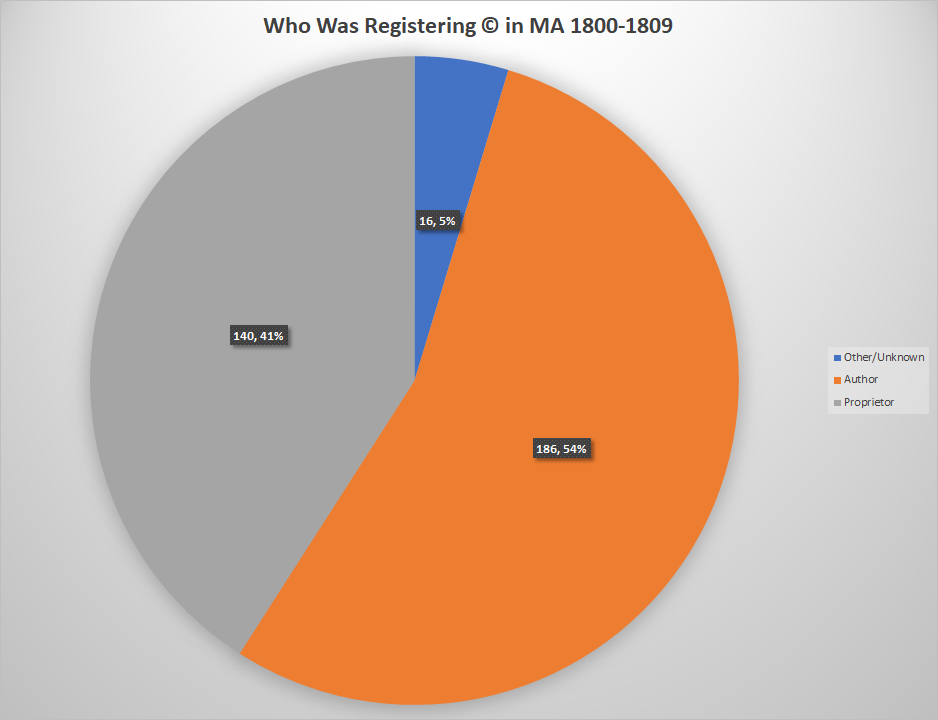

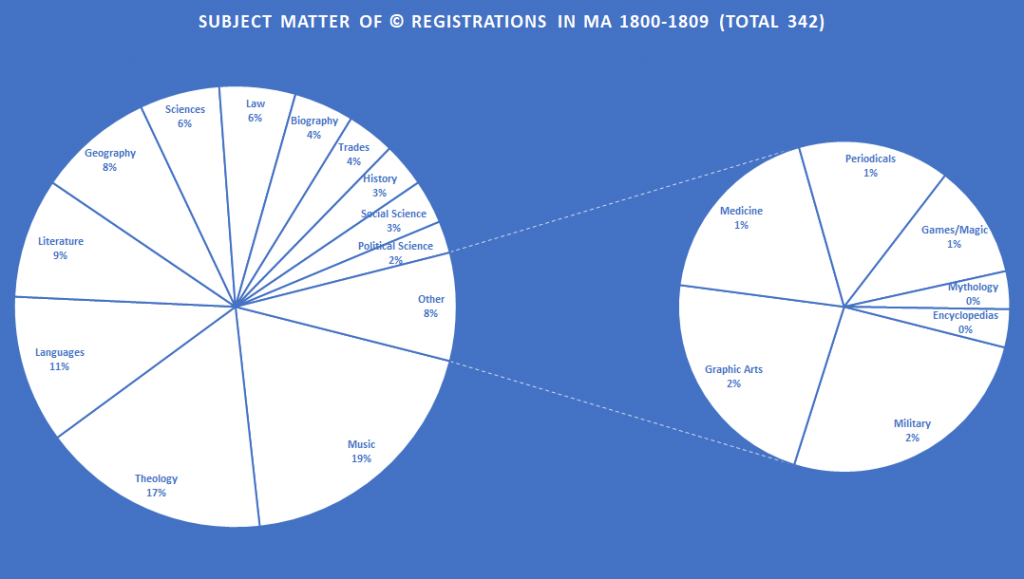

So, that tells us about the volume of copyright registrations, but not what was being registered. Unfortunately, there we hit a bit of a brick wall – these are mostly tallies of pages, not descriptive data. I have created a resource of all known transcriptions of the pre-1870 records, although that only covers a small fraction of the records. I also expect the recent upload of the pre-1870 title page collection is ripe for study, as are the pre-1870 collections of “found” records I’ve shared. However, the study mentioned previously by Ruth Shaw Leonard goes into more detail, and actually explores what was registered in Massachusetts in the years of 1800-1809, and who was doing the registration. This is all out of a total of 342 registrations.

For the above chart I’ve combined some categories, here is the actual chart she provides:

| Registrant | Number |

| Authors | 143 |

| Authors (called Proprietors) | 37 |

| Printers | 30 |

| Publishers or Booksellers | 105 |

| Relatives of Authors | 6 |

| Sponsoring Organization | 5 |

| Other/Unknown | 16 |

Perhaps even more interesting, she also breaks down what was being registered, which I’ve represented in a chart here:

Once again, this is actually a simplification of her list; I’ve included the entire list from her study below. The large amount of music is particularly interesting, especially given that music was not formally added to the federal copyright law until 1831.

- Biography……………………………………………………………. 12

- Funeral Sermons ……………………………………….. 3

- Geography and Travels ………………………………….. 16

- Maps and Charts ………………………………………… 7

- Pilot Charts ……………………………………………………. 6

- History ……………………………………………………………………… 11

- Languages

- English Language …………………………………….. 32

- Latin Language …………………………………………. 5

- Laws ……………………………………………………………………………… 15

- Trials …………………………………………………………………… 4

- Literature

- Drama ………………………………………………………………………….. 5

- Fiction ………………………………………………………………………….. 8

- Humor ………………………………………………………………………….. 1

- Juvenile Literature ……………………………………………………….. 6

- Oratory ………………………………………………………………………….. 1

- Poetry ………………………………………………………………………….. 5

- Miscellany of Literature …………………………………………. 4

- Medicine ……………………………………………………………………… 5

- Military Art …………………………………………………………….. 7

- Music

- Instruction Books …………………………………………………. 4

- Instrumental Music ………………………………………….. 3

- Sacred Music or Psalmody ……………………………………… 50

- Songs and Song Books (except Sacred Music) …………….. 9

- Mythology ………………………………………………………………………… 1

- Political Science ………………………………………………………………………. 8

- Recreative Arts

- Games and Magic……………………………………………………………. 3

- Sciences

- Arithmetic …………………………………………………………………………. 11

- Astronomy ………………………………………………………………………….. 1

- Maps and Charts ………………………………………………………… 2

- Navigation ………………………………………………………………………….. 6

- Soclal Sciences

- Crime and Criminals …………………………………………………………… 2

- Economics

- Banking ……………………………………………………………….. 2

- Tables or Duties …………………………………………………….. 2

- Education ………………………………………………………………………….. 1

- Freemasons ………………………………………………………………………. 2

- Social ethics………………………………………………………………………….. 2

- Theology ………………………………………………………………………………… 53

- Catchetism (Primers) ……………………………………………………… 4

- Useful Arts

- Bookkeeping ……………………………………………………………………… 2

- Building and Carpentry………………………………………………………………………….. 3

- Farriery………………………………………………………………………….. 1

- Penmanship …………………………………………………………………… 6

- Forms of Material

- General Encyclopedias……………………………………………………. 1

- Periodicals ……………………………………………………………………… 4

- Engravings and Designs……………………………………………….. 6

- Total………………………………………………………………………………….. 342

- The 2019 Annual Report lists the 150,000 number as being 1790-1869, but that isn’t technically correct – the 1870 Act entered force on July 8, 1870, and we estimate that there were 6,235 registrations in the District Courts prior to that date in 1870. Also a few later, because it seems compliance with the act was a little spotty in the first year. ↩