Product Labels and the Origins of Copyright Examination

A foundational story about the development of copyright in America is the question of whether product labels could – or should – be protected by copyright. As far as I can tell this question marked the beginning of denying copyright registration on the grounds of subject matter, and I think is an important story to tell for understanding a number of current debates regarding copyrightability, and also serves as an antecedent to the modern copyright examination system. I’ve written about this story some in the past, in my 2012 article Reimagining Bleistein: Copyright for Advertisements in Historical Perspective, but it’s worth highlighting this story separately from the broader narrative in that piece, and I’ve found some additional parts to this story since I published that piece.

Although the 1790 Copyright Act only prescribed a limited species of works for protection, for instance omitting music from the list of protected works, Courts would quickly hold that a musical work or even a single sheet of paper could be registered for copyright as a “book” (or after 1802, a “print”). This matches a general early tendency to be liberal in what could be registered. However, in 1848 Justice McLean, riding Circuit, held in Scoville v. Toland that a label that reads “Doctor Rodgers’ Compound Syrup of Liverwort and Tar. A safe and certain cure for consumption of the lungs, spitting of blood, coughs, colds, asthma, pain in the side, bronchitis, whooping-cough, and all pulmonary affections. The genuine is signed Andrew Rodgers” is not subject to copyright. Justice McLean reasoned that the purpose of the label was only to identify the product, and it communicated nothing beyond its association with the product – and accordingly copyright law would not protect it. In the 1850s, the copyright records show a clear upwards trend in registrations of product labels for copyright protection, and coupled with the Scoville decision, this led some to question whether product labels were protected by copyright – especially regarding patent medicines.

A letter from the Clerk of the US District Court for the Northern District of New York (Aurelian Conkling at the time), published in the New York Journal of Medicine and Collateral Sciences in 1856, highlights the problems these so-called “patent medicines” posed for Clerks who were asked to register their labels for copyright (recall that the District Court Clerks were responsible for copyright registration until 1870). The letter explains that the usage of “patent” was sardonic, since “these notrums not truly patented, the secret of their preparation being studiously withheld in defiance of…our Patent Laws.” Rather, these patent medicines would attempt protection by registering their labels for copyright and then bringing suit against competitors for infringement of the copyright. Mr. Conkling had been refusing to grant copyrights for patent medicine labels for several years at this point.1 Conkling further opined that:

Congress did not intend to prevent the imitations of the stamps and labels of any manufactured article, or goods, or merchandise [under copyright law]. That is a subject of such extensive interest and importance, that, if it had been the intention of Congress, to embrace it in the provisions of the law, that intention would have been distinctly and unequivocally manifested.

In response to a letter from Mr. Conkling, the State Department (responsible for the administration of copyright until 1859) issued a circular stating that “inasmuch as mere labels are not comprehended within the meaning” of the copyright law, clerks were instructed to “refuse, in all cases, to record or issue a certificate for the same” under the copyright law.

In 1859, copyright responsibilities were moved to the Interior Department, which delegated them to the Patent Office (although registrations themselves remained the responsibility of the clerks of the district courts). Shortly after this act was put into effect the Patent Office put out a circular to the same effect as the State Department circular a few years earlier, specifically directing the district courts not to register “stamps, labels, and other trade-marks of any manufactured articles, goods, or merchandise” because “the acts of Congress relating to copyright are designed to promote the acquisition and diffusion of knowledge, and to encourage the production and publication of works of art,” and thus labels were not “embraced within the meaning of the [copyright] acts.” Thus a label, no matter how artful, could not be registered as copyright, but might be registered as a design patent.2 It’s likely that the list of labels, trademarks, etc that the Patent Office produced in 1859 and supplemented in 1861 stemmed out of the release of this circular.

In spite of these clear pronouncements, compliance with these circulars varied. In a Series of Letters from 1864-1866 (PDF, 4 MB, from the miscellaneous files of copyright records in the Rare Book Room of the Library of Congress), a successor as clerk of the District Court for the Northern District of New York complained that he was getting many requests to register labels, and that a common complaint was that the Southern District of New York had no such compunctions about issuing copyright registrations for product labels. Given that the Southern District had a much higher volume of copyright registrations that is perhaps understandable that less attention would be paid at the Southern District (there are 4,484 pages of copyright records microfilmed from the Northern District from 1820-1870, compared with 54,822 from the Southern District for the same period). Perhaps more notable is that aside from the Northern District of New York, there’s no real record of other courts refusing to register labels (that I’ve found – the copyright records of many Courts are overflowing with labels by the end of the 1860s).

Nonetheless, the Copyright Office issued a Circular in response in 1866 (PDF, 1 MB, this copy from the NJ 1846-1870 Copyright Files at the Library of Congress) making clear that their views on whether labels were protected by copyright had not changed. The language the Commissioner of Patents used is a development from Justice McLean’s opinion in Scoville v. Toland 18 years earlier, and it has a whiff of the concept of aesthetic separability that was argued in Mazer v. Stein 88 years later.

As all the acts of Congress related to copyrights are designed to promote the acquisition and diffusion of knowledge, and to encourage the productions and publication of works of art, it has always been held that stamps, labels, and other trade-marks of any manufactured article, goods,or merchandise are not embraced within the meaning of the acts. When any production is issued as an object of art, having value in itself, and intended for sale as such, it properly comes within the provisions of the copyright law; but when, however artistically executed, it is not produced for sale as a work of art, but is designed to be affixed in the manner of a label to a manufactured article, it then plainly falls under the act relating to patents for designs, and consequently cannot be protected by copyright.

As noted, despite repeated encouragement from Washington, it does not seem that other Districts followed the lead of the Northern District of New York. As I tell in much greater detail in my article, when copyright was centralized at the Library of Congress in 1870, the Library was quickly overwhelmed with applications to register product labels for copyright, and in 1874 the Librarian convinced Congress to pass a law transferring responsibility for registering labels to the Patent Office, where they would be a sui generis form of intellectual property registered along the same rules as those for registration of copyright. The statute attempted to create this entire new form of intellectual property in one paragraph of statutory language, and hijnks predictably ensued, including a case where the Patent Office repeatedly ignored mandamus from what is now the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals to register labels without examination.

The decision of the Supreme Court in the Trade-Mark Cases in 1879 (holding the 1870 Trademark Act unconstitutional) did not stop the process of label registration, but the Supreme Court’s 1891 holding in Higgins v. Keuffel that a label for india ink was not protected by copyright did pause the system of label registrations with the Patent Office for a number of years.

The label at issue in the case of Higgins v. Keuffel, along with its registration information.

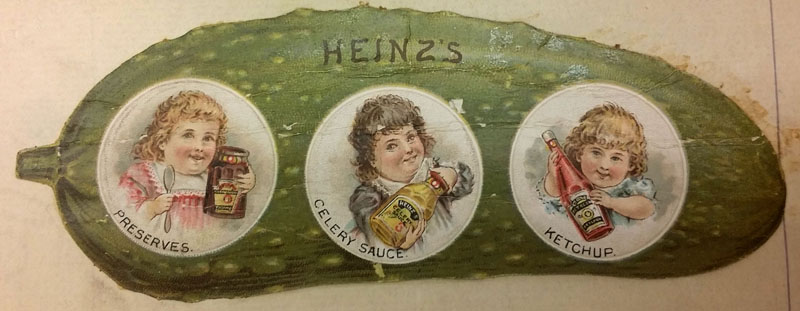

However, in 1893 the Comissioner of Patents ruled that labels could be registered, provided they were of sufficient originality to meet the authorship requirements of the copyright clause (which the label from Higgins did not). However, the Comissioner held that the advertisement at issue in Ex parte H.J. Heinz Co., 62 O.G. 1064 (Comm’r Patents, 1893) was of sufficient originality to qualify for registration as a label.

The product label Heinz successfully registered following an appeal to the Commissioner of Patents in 1893.

Somewhat surprisingly, commercial labels and advertisements would not be returned to the jurisdiction of the Copyright Office until 1940. The story – especially after 1874 – is told in greater detail in my article, but I’ve brought it up a few times lately, and it seemed to be worth highlighting.

- Apparently the denied copyright registrations included a “elixir of life” as well as a “diarrhoea cordial.” Letter at 423. Surely the latter would test the limits of aesthetic non-discrimination even today. ↩

- This paragraph is copied essentially verbatim from pg. 352 of my 2012 article. What’s next is new, though. ↩