Looking for Copyright Records in Old Florida

At the 2022 Copyright Society Annual Meeting, I made an offhand comment that Florida wins the prize for fewest copyright registrations before 1870 (of states admittedly substantially before 1870) with zero. And I and the Floridian I was chatting with had a good laugh, because Florida. But I got to wondering if that was really true, and the answer is no – I’m pretty sure I discovered the first Florida copyright. That said, that zero was only slightly off, and the search shows just how difficult completeness is.

As most reading this blog presumably know, one of my long-term projects is to bring together all of the pre-1870 copyright records. The bulk were transferred to the Library of Congress in 1870, which has almost completed their project to scan them (what’s left is mostly Pennsylvania records, which are currently in progress). In 2016-2017 I tracked down most of the other records which never made it to the Library, which I’ve blogged about before. However, there are still places where I couldn’t find records. Some of them are places where records clearly exist but haven’t yet been found – I’m thinking specifically of Connecticut 1790-1804, Maryland pre-1831, DC pre-1845, Louisiana pre-1851 (mostly), Texas until after the Civil War, and Ohio 1829-1842 (record book documented in 1933 schedule, now missing). For these records it’s simply a matter of finding them, and accepting their loss otherwise. The “second set” kept by the State Dept. and then Interior from 1831 onward covers some of these eras. For other places, the question becomes how much exists, and how early. Even if states existed as of a certain date, copyright registrations were rarely immediate. Florida presents an extreme case, and a window into the difficulties of truly tracking down every single registration.

Florida became part of the United States in 1821, but did not become a state until 1845. Even after it became a state the population remained low – as of 1860 it was under 150,000 people – and almost half of them were enslaved. Generally speaking slavery seems to have had a strong negative impact on literary production as measured by copyright registrations (even when only considering white population), and states with smaller populations also produced fewer copyright registrations per capita. Florida thus was something of a perfect storm in that regard. The Florida federal courts can be a bit confusing – as a territory there was an Eastern, Middle, Western, Apalachicola, and Southern district of the Superior Court, but those courts do not neatly correspond to the modern Northern, Middle, and Southern Districts of the US District Courts for Florida.

Nonetheless, I followed the leads supplied by Douglas C. McMurtrie in his The Beginnings of Printing in Florida to see if I could find any works with copyright notices. The earliest works printed were law books which surprisingly lacked copyright notices, and newspapers which unsurprisingly lacked them. However, in 1831, William Mortimer Smith and Edward R. Gibson published a novel at the press of the Florida Courier in Tallahassee.

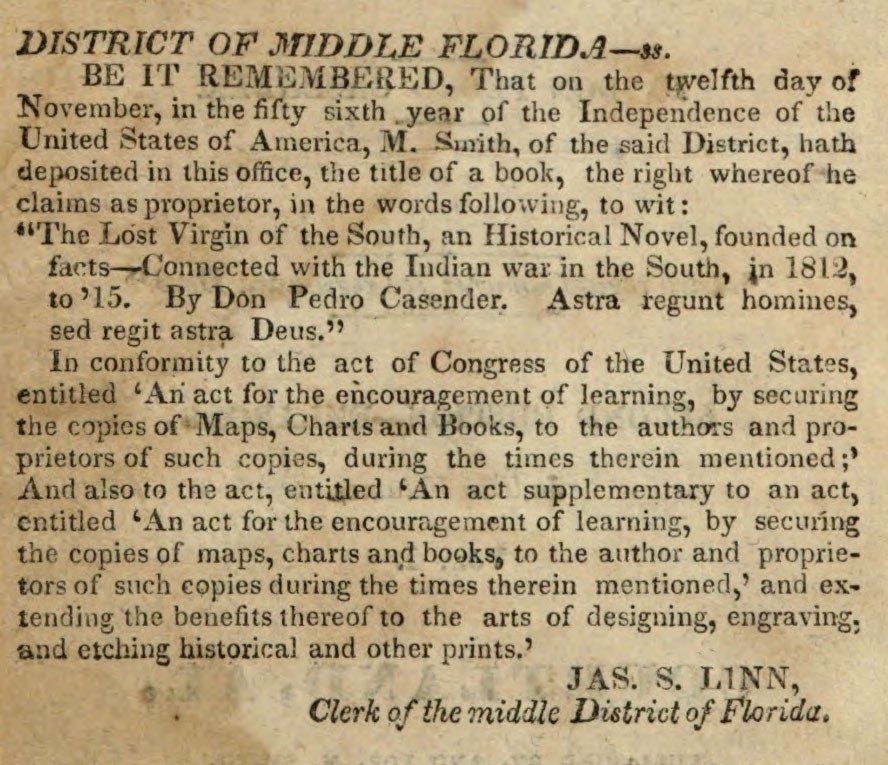

The novel, entitled The Lost Virgin of the South, An Historical Novel, Founded on Facts, Connected with the Indian War in the South, in 1812 to ’15, was attributed to a Don Pedro Casender, but actual authorship is unclear (the second edition, printed in Alabama and the source of the above image, is here). The notice is a full transcription of the copyright registration, as required by the Print and Notice Act of 1802, This is fortunate, as the National Archives does not hold any records of the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of the Territory of Florida, which sat in Tallahassee. The 1831 Copyright Act, requiring only a much shorter notice, had been in force since February of that year, but one suspects the court in Tallahassee was still using an old copy of the law.

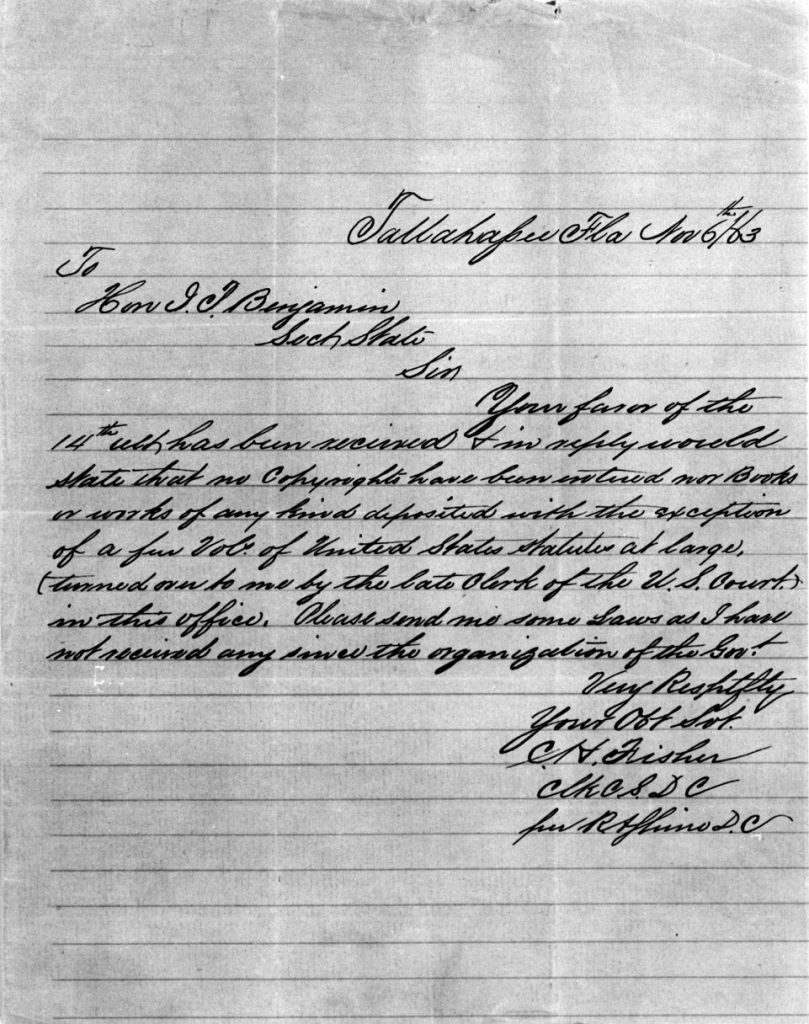

So, I’d found one registration, but could there be more? I was going to Atlanta anyway, and I’d been meaning to visit the National Archives location there, which holds the records for the Florida federal courts. I looked up what records exist of federal courts in Florida before 1870, and saw they had records from both Tallahassee and Pensacola from 1847 forward, so I had a chance to review them. And I found…nothing. Not a single record of a copyright registration. This was reinforced by a letter sent by the clerk of the Confederate District Court in Tallahassee in 1863 (the Confederacy used a modified version of the 1831 Copyright Act, save for notably providing for international copyright as an attempt to curry favor with England).

As can be seen, the clerk of the Tallahassee Court indicated in 1863 that no registrations had been made or new books received, and that he had no institutional memory of any registrations ever being made. It’s not clear how long that was – it likely only is since secession – but still notable.

Using the Library of Congress catalog, I was able to find one other book with a copyright notice for Florida, “Florida. Its climate, soil, and productions; with a sketch of its history, natural features and social condition. A manual of reliable information concerning the resources of the state and the inducements which it offers to immigrants.” The book indicates that it was deposited in the clerk’s office for the Northern District of Florida in 1868. There were no other records of non-newspaper publications from Florida that have copyright notices before 1870.

So, two is more than zero. And there may have been more, either published works that I missed, or unpublished works which were registered but never produced. The whole exercise illustrates I think the difficulty of certainty regarding the pre-1870 records. The vast majority are still accounted for, a decent percentage of what’s left may yet be found, but there are some states like Florida where not all records survived, and even if they survived in a general-purpose record book, it’s going to be looking in a haystack for a possible needle. On the flip side, it’s a reminder that even in states where no records survived, and where the clerks of the court said they hadn’t gotten any copyright registrations, it doesn’t mean none were made.

Does it seem appropriate that the registration may list a false author? Because, Florida.